The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

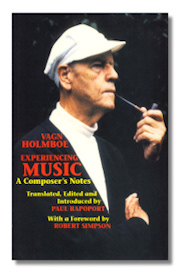

Book Review

Book Review

To me, the Danish composer Vagn Holmboe has created many of the outstanding symphonies, concerti, and string quartets of our time. Thanks to the label BIS, you can now find all of his symphonies on CD. One senses in the music a great power which comes from an Apollonian sense of order. The pieces don't just fit, they fit so snugly, with such inexorable, Beethovenian logic, that the joins don't show. It's as if you could sing a movement from beginning to end, and yet, the music is made up not of songs, but of little note-y bits varied and recombined into continually-varying kaleidoscopic patterns. Nevertheless, one experiences them not as a succession of pretty pictures, but as an argument with great dramatic thrust.

The usual rap one hears against Holmboe hits at what some perceive as emotional distance, but then our time tends to value the tortured soul over the balanced one. Indeed, we sometimes mistake the wounded for the profound, an inherited Romantic attitude that says great souls suffer great pain. In other times, people valued the balance of wisdom, and I hear that attitude in the music of Mozart. No matter how "unsettled" it gets – and, compared to Wagner, it's not all that much – the whole conveys poise. I hear the same characteristic note in Nielsen, Ravel, and Hindemith – a susceptibility to the rapture in the presence of the "sensuous form."

It's dangerous to generalize about a writer whose language you don't read, but I get the same feeling from Holmboe's prose – that is, I recognize the mind of the essay writer as similar to the mind of the composer of the symphonies. The literary English style strikes me as capable, but not all that interesting in itself. I have no idea whether this comes from a self-effacing translation or from Holmboe's Danish. However, the content is extremely interesting. Holmboe addresses his book, not to the specialist, but to the general intelligent reader, although even a specialist could learn something from it. You don't need to be able to read music to understand it. There is no musical type or even one musical tech term. The meat of the book is a longish, multi-part essay called Det uforklarlige (Music – The Inexplicable), conceived by the author as a kind of prose symphony. The course of argument moves very much like a Holmboe symphony, where a small set of ideas becomes transformed and deepened in new contexts. Indeed, Holmboe lays out the essay in "movements": "Prelude," "First Movement: The Composer," "Second Movement: The Performer," "Third Movement: The Listener," "Fourth Movement: The Inexplicable," and "Postlude." From even this bare recital, one can see that Holmboe conceives of music in a social context – a cooperative venture, if you will. He concerns himself throughout with the perception of music as something alive: he speaks of music's "life" or "living music," as distinct from the composer's conception or a particular performer's interpretation or the psychological vagaries of a particular listener at a particular time. Nevertheless, he takes care to draw the relationships among all three agents in the creation of music that comes alive. This life remains inexplicable, miraculous, even – to quote Holmboe – "magical." Holmboe extends his model to include the culture at large, which reveals his belief in music as a social force, with interactions and responsibilities among artists and civilians. Along the way, he touches on such topics as how at least one composer goes about his job, the question of revision, faithfulness to the letter and to the spirit, snobbery, the relation of folk music and art music, the necessity (or not) of special training, how one listens, how one experiences music, views on the "ideal listener," the relationship of intellect and emotion, and so on – all topics that seem to interest hard-core classical-music fans, at least from time to time.

I admire the author for many things, not the least of which is his attempt to convey the "normality" of composing. I would think that Holmboe, of anyone out there, could appropriate for himself special privileges – the demand that one recognize his superior penetration, the divine nature of his inspiration, and so on – but he never does. Composing is work (a lot of work), the lucky, even inexplicable, accidents that arise during the process, the breakthroughs, born of thought and trial, where the composer finally sees how the piece should go. I also admire the fact that he admits his ignorance, rather than engage in metaphysical jiggery-pokery. Holmboe wants to persuade you by what he says, rather than by who he is, even though the essay contains of necessity the first-hand experience of a superb musician. In short, the essay comes across as wisdom dressed as modesty.

Experiencing Music also contains "On the Experiencing of Time" (from Holmboe's book Interlude; "Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms," a little meditation on recorded vs. live music; a brief reminiscence and reflection on Carl Nielsen; "Haydn and Tradition," which considers how new composers confront and reckon with the past; "Human Responsibility and Artistic Freedom," which of course takes up again Holmboe's social vision of art.

Thanks again to Toccata Press for a stimulating publisher's list. At a time when books "about music" tend to run to gossip, to shop talk, or to basic introductions, this publisher offers stimulating works addressed to the general adult public.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz.