The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

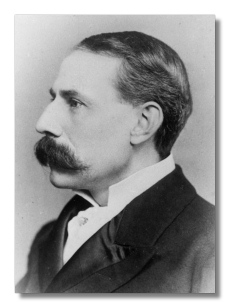

Edward Elgar

(1857 - 1934)

Edward Elgar (2 June 1857 - 23 February 1934), considered in some quarters the epitome of the British establishment, felt himself (like his contemporary, Gustav Mahler) triply an outsider. He worked most of his early life in the north of England, far from the great musical center of London. He was the son of a piano tuner, a man "in trade," at a time when and in a country where such things mattered. Finally, he was Catholic in a strongly Protestant England.

Elgar attended a local Catholic school but left at 15 to work in a solicitor's office. One can't imagine a boy with his day-dreamy temperament becoming a lawyer. Indeed, he left after a year to work as a musician in a variety of odd jobs, including church organist, teaching music to the staff of a local insane asylum, playing violin in the Three Choirs Festival orchestra, and working in his father's shop. He never held a permanent musical post. Beyond a year of violin lessons, he had no formal musical training.

He began to compose while still a boy and largely taught himself through the practical method of writing for the local church and the local ensembles he headed, of studying scores in his father's shop, and of playing continental works in various orchestras. He became a member of the Birmingham orchestra and played under Dvořák in 1881. His early orchestral music was performed by this ensemble. From 1870 on, he made regular jaunts to London and there heard Wagner, Schumann, Brahms, and Liszt.

In 1883, he became engaged to a girl named Helen Weaver, but it fell through, possibly because his prospects were so poor. However, in 1889 he met and fell in love with one of his piano students, Caroline Alice Roberts, a woman ambitious for her writing and socially middle-class. She accepted him, and once she had converted to Catholicism, they were married within the year. A remarkable person in her own right, she essentially managed his life to make it possible for him to compose, and she influenced the course of his music. It was one of the strongest marriages in the history of music.

In 1890, the Elgars moved to London, so that Edward's music could conquer it. He secured a couple of performances of what we now consider minor, though charming work. However, he also composed the overture Froissart for the Three Choirs Festival and conducted it in Worcester. London, however, remained uninterested and unconquered. After a year, the Elgars had to slink back north to Worcestershire.

In the north, however, Elgar's opportunities continued to grow, largely thanks to the Three Choirs. Elgar completed a series of cantatas – The Black Knight (1893), The Light of Life (1896), and Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf (1896), the last of which was excerpted in London. In 1897, Elgar composed an Imperial March for Queen Victoria's Jubilee, and in 1898, the Queen accepted Elgar's dedication of the cantata Caractacus. Most of these works received London performances and, although largely neglected now, contributed considerably to Elgar's English reputation. He began to move in the professional circles of the prominent English musical lights of the day: among them, Arthur Sullivan, Charles Hubert Parry, Charles Stanford, and Granville Bantock.

However, Elgar's big artistic breakthrough came with the composition of his Variations on an Original Theme ("Enigma") (1899), considered by many the finest piece of English music up to its time since the death of Henry Purcell. The work varies a theme which begins with the notes C-A-D-B and which is labeled "Enigma." "Enigma" originally applied only to the theme, rather than to the entire variation set. Elgar dedicated the piece "to my friends pictured therein," and each variation portrays a member (in one case, a member's dog) of Elgar's Worcestershire circle. Elgar even includes as the final variation a portrait of himself, and in many ways it's the strangest of the set. In spite of its glorious bravado, Elgar, in his comments on the piece, referred to the doubts about his future entertained by his friends. This embracing of simultaneous extremes was a fundamental part of Elgar's personality: in this case, hopes for success were always accompanied by the expectation of humiliation. Hans Richter conducted the premiere in London and subsequently in Germany. Elgar's blazing mastery of the orchestra was something, if not entirely new, then supremely individual. In 1900, Cambridge awarded him an honorary doctorate. Richard Strauss became a fan. Most writers date Elgar's international reputation to the Variations' premiere.

From that point on, Elgar entered his greatest musical phase. He followed up the Variations with the orchestral song cycle Sea Pictures (1899), the oratorios The Dream of Gerontius (1900), The Apostles (1903), and The Kingdom (1906), the Cockaigne Overture (1901), the Pomp and Circumstance marches (1901), the overture In the South (1904), Introduction and Allegro for string quartet and string orchestra (1905), two symphonies (1904, 1911), a violin concerto (1910), the symphonic poem Falstaff (1913). He had enjoyed a remarkable run and had become the pre-eminent British composer. In 1905-06, he delivered a controversial series of eight lectures on the current state of British music in which he criticized British composition, British musical training, and public taste.

World War I, however, severely depressed him the point of dampening his creativity. For the most part, his "war work" was adept, but not especially deep. The end of hostilities released the springs, however, and he produced a magnificent trilogy of chamber works (a piano quintet, a violin sonata, and a string quartet) as well as his great testament of the war, the cello concerto (1919). This new burst of energy didn't last. In 1920, Caroline Alice Elgar died and, with her, Elgar's concentration for composition. He had fourteen more years to live, and his completed works consist of incidental music and light suites, small-scaled masterpieces based on music he had written decades before. Two major works lay incomplete at the time of his death: an opera, The Spanish Lady, and a third symphony. Both have been completed, with varying results. Percy Young's completion of The Spanish Lady essentially makes performable the scraps Elgar left behind (Elgar tended to compose in scraps), rather than provides a performable opera. Anthony Payne's completion of the third symphony creates for us the illusion of a new Elgar symphony. It is a magnificent achievement, on the order of Deryck Cooke's completion of the Mahler Tenth.

Elgar, who looked something like a Colonel Blimp or a country squire, had a complex personality which comes out in his music. He tended to bounce between extremes. He had given his life to music but hated to talk about it so much that he affected to know nothing about it. He turned out a slew of salon pieces and parlor songs to earn money and hated himself for its incursion on time for the ambitious work of which he knew himself capable. Invited to a formal luncheon as a great national figure at the time of Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, an invitation he had moreover previously accepted, he sent his regrets, saying, "You would not wish your board to be disgraced by the presence of a piano-tuner's son and his wife." His letters on the war condemn humankind to hell, while weeping for the deaths of field animals. He kept to his Catholicism as his belief in it, especially after the death of his wife, dwindled.

The music, too, races between extremes. Indeed, a significant part of Elgar's achievement is the fashioning of a language flexible enough to handle both subtle and radical shifts of mood without the music falling apart. For example, the opening to the first symphony, with its famous "motto theme" redolent of passing empire, fades into the turbulence of the symphony proper without a bump. Elgar takes this kind of juxtaposition even further in his second symphony, which he headed with a quote from Shelley: "Rarely, rarely, comest thou, Spirit of Delight."

The critical reception of Elgar's music has a fascinating history, even within Britain. The end of the Great War brought a backlash. Elgar was regarded in influential quarters as a sentimental jingo mindlessly celebrating empire and war, a view promulgated in an influential (and notorious) article by E. J. Dent. Critics characterized his music as overblown "loose, baggy monsters," incoherent as a three-volume Victorian novel. This colored Elgar's reception for decades. Assiduous scholarship, however, has exposed the half-truths behind this image and has given us a clearer picture of the man and his music. Even better, since the Sixties, the younger generation of musicians have taken him up and have begun to explore the obscure corners of his output. We have begun to hear Elgar without baggage. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

Concerto for Cello

Concerto for Cello

- Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85/EMI CDC7473292

-

Jacqueline Du Pré (cello), John Barbirolli/London Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85/CBS MK39541

-

Yo-Yo Ma (cello), André Previn/London Symphony Orchestra

- Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85/Virgin VC75952112

-

Steven Isserlis (cello), Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra

Concerto for Violin

- Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61/EMI CDC7472102

-

Nigel Kennedy (violin), Vernon Handley/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61/Naxos 8.550489

-

Dong-Suk Kang (violin), Adrian Leaper/Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra

- Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61/RCA Gold Seal 7966-2-RG (mono)

-

Jascha Heifetz (violin), Malcolm Sargent/London Symphony Orchestra

Enigma Variations

- "Enigma" Variations, Op. 36/Telarc CD-80192

-

David Zinman/Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

- "Enigma" Variations, Op. 36/Virgin VJ7596432

-

Andrew Litton/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Pomp & Circumstance Marches

- 5 "Pomp & Circumstance" Marches, Op. 39/Denon CO73534

-

Charles Groves/Philharmonia Orchestra

- 5 "Pomp & Circumstance" Marches, Op. 39/Chandos Collect CHAN6504

-

Alexander Gibson/Scottish National Orchestra

Symphonies (

Symphonies ( 1, 2)

1, 2)

- Symphony #1 in A Flat Major, Op. 55/Philips 416612-2

-

André Previn/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #1 in A Flat Major, Op. 55/EMI CDM7640132

-

Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #1 in A Flat Major, Op. 55/RCA Red Seal 60381-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #2in E Flat Major, Op. 63/EMI CDM7640142

-

Adrian Boult/London Symphony Orchestra

- Symphony #2 in E Flat Major, Op. 63/Chandos CHAN8452

-

Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra

- Symphony #2 in E Flat Major, Op. 63/RCA Red Seal 60072-2-RC

-

Leonard Slatkin/London Philharmonic Orchestra