The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Svoboda Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

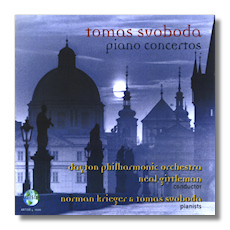

Tomás Svoboda

Piano Concertos

- Concerto for Piano #1, Op. 71

- Concerto for Piano #2, Op. 134

Tomás Svoboda, piano (1)

Norman Krieger, piano (2)

Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra/Neal Gittleman

Artisie 4 1006 63:00 2001

Svoboda's piano concerti are unequal in length but both have, in addition to melodic appeal, interesting use of instrumental resources, both that of the soloist and of the orchestra, wide range of dynamics and tempi, and tremendous rhythmic excitement. Svoboda's acknowledged early influence by Martinů particularly shows in the rhythmic-driven momentum of many passages.

Concerto #1, from 1974, is in a single, nineteen-minute movement. Thematically, it is in eight sections, each intended to get further and further away from the piano's principal theme before a return at the end to the place it started. Svoboda, who strongly believes in the expressive nature of music, likens this to distant travels to new and exciting places but in a full circle back to one's homeland. Commissioned by the Chamber Music Society of Oregon, the scoring is for strings, timpani and woodwind sextet (not further specified, but my ears tell me this includes a trumpet.) At the première, the entire work was repeated as an encore.

The introduction begins with a bouncy string melody, with woodwind, brass and timpani before the piano enters. Forceful and vigorous proceedings yield to an extended section or series of sections featuring the woodwinds, often staccato, sometimes under flowing string playing, leading to an interlude for woodwinds alone, notably the bassoon, without the piano playing at all for about a minute and a half. At almost exactly the midpoint of the concerto a drumroll initiates a more and more vigorous momentum and force: presto tempo, pounding dynamics, and bouncy rhythm. After a change of pace for the cadenza, the conclusion is exciting, headlong exuberance.

Concerto #2 is nearly three quarters of an hour in duration with a twenty-five minute opening movement, allegro ma non troppo. The short middle movement is marked lento recitativo and the finale is presto. It premièred in 1989 with garrick Ohlsson the soloist and Thomas Conlin conducting the West Virginia Symphony, which commissioned it for its 50th season. Svoboda reports that the work originated in intense and contrasting feelings centering on a sense of dislocation he experienced in Frankfurt after his first visit to Czechoslovakia in 21 years. The piano solo, for Svoboda, represents his response to the hearing of cathedral bells on that occasion.

Those bells can be heard unmistakenly with the entrance of the piano after a fiercely stormy and lengthy orchestral introduction lasting close to three minutes. When proceedings quiet down there is a lyrical melody for the oboe, but it is mostly the piano we hear until the tempo picks up. Some of the orchestral accompaniment is particularly interesting: high woodwinds over prominent basses, quick-step motion over deliberate pacing by the piano, brass flourishes with drums over emphatic playing by the soloist, lighter and faster piano against gestures by the strings, an oboe heard over the timpani, tubular bells adding to the piano's bell-like tones. Some angular rhythms, snare drums and very loud dynamics create considerable tension, and the piano returns to the kind of emphatic sound that marked its first entrance. The second half of the first movement is mostly fast and loud, a bit of it reminding me of Bartók. Before the end, though there is some quiet piano and a high oboe is heard. A final orchestral onslaught gives way at the end to a very quiet conclusion with, this time, hign notes for a solo violin.

The lento movement begins with a bassoon solo (significant enough for the soloist, Jennifer Kelley Speck, to be credited on the disc), which returns. Most of the movement is quiet, slow, meditative: in a word, lovely. There is some high, shimmering string accompaniment preceeding an increase in tension and louder playing especially by the piano. After a third bassoon solo, and soft piano playing, a very quiet clarinet is heard as the music dies away.

The thirteen-minute presto finale is very vigorous and exciting: fierce, pounding, thumping rhythms, driving pace, and rushing strings; emphatic, staccato percussion; loud brass; emphatic playing by the soloist. Yet this is relieved by some some relaxed, quiet moments: light rapid piano playing, some legato and some shimmering string passages, a touch of tinkling percussion, and quiet woodwinds. At one point the piano plays quietly while accompanied by slow but emphatic drumming. In its turn the piano is emphatic during what is a thrilling conclusion to the piece.

As these descriptions show, there is tremendous variety in Svoboda's music, but I never ask myself, where is this change in mood coming from? The transitions between rising and falling tensions never sound forced. This is one of the things I want to say about Svoboda's writing.

The performances on this disc are superb. Both soloists have tremendous power and skill to spare. The orchestra, under Neal Gittleman, whose performances with the Milwaukee Symphony, where he was Associate and Resident Conductor for nine years, were much admired by me and others, plays very well. The tempos are satisfying and always apt.

Availability: http://www.normankrieger.com/CD_pages/Svoboda.htm

Copyright © 2007, R. James Tobin Copyright 2007 by R. James Tobin