The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Harris Reviews

Piston Reviews

Schuman Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

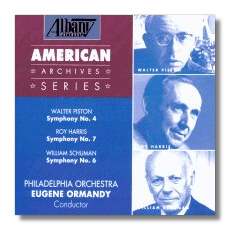

Eugene Ormandy

American Symphonies

- Walter Piston: Symphony #4

- Roy Harris: Symphony #7

- William Schuman: Symphony #6

Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy

Albany TROY256 MONO 72:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: Classic accounts from The Other Ormandy.

Ormandy's image as a high-class purveyor of schmaltz has overtaken his actual work. Among other things, he early on championed the symphonies of Mahler, when Leonard Bernstein was a teenager. He also did quite a bit of modern music. In fact, I first became aware of American music as such through an Ormandy concert: MacDowell's Piano Concerto #2, Cowell's Hymn and Fuguing Tune #2, excerpts from Copland's Tender Land Suite and Sessions's Black Maskers Suite, and the finale of Creston's Symphony #2 – not only for the time, but even now not the usual suspects.

Like any conductor, Ormandy had his strengths and weaknesses. He was a superb colorist. A violinist himself, he got wonderful sounds from his strings, and he made sure that the winds and brass of the Philadelphia were as good as any. He also had a great sense of musical "narrative" and rhetoric. He could "tell the tale" of a piece better than most. His rhythm, on the other hand, was notoriously slack. The precision of the Cleveland, the Berlin Philharmonic (under someone other than Karajan), and the Chicago eluded him. He had trouble with highly contrapuntal music. His recording of Hindemith's Mathis der Maler Symphony, although immensely popular, turned Hindemith's precisely-judged textures and counterpoint to tapioca. On the other hand, there were pieces he just about owned – the popular Tchaikovsky and the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique, for example. Furthermore, every now and again he would surprise you with wonderful accounts of scores you'd have thought outside his purview. I think especially of his strong Shostakovich Symphony #13, a blistering Orff Catulli Carmina, and his performance with Serkin of the Beethoven Piano Concerto #4, the latter unsurpassed (even by those with bigger Beethoven reputations) in its communication of architectural detail and great poetry.

American-music freaks like me have long treasured Ormandy's Piston and Schuman recordings, released (and even re-released) on the same Columbia LP, not least because these were the only recordings of some wonderful music. I've not heard the Harris before, although Ormandy recorded it in 1955. The fourth is one of Piston's finest, managing to combine passion and elegance. The opening "Piacevole" movement never fails to rapture me out. Ormandy and the Philadelphia perform at their typical rhythmically loose, but this is a noble sweeping, powerful account and, in the long view, beautifully shaped and singing.

At one point, Roy Harris enjoyed an enviable reputation as a leading American composer, right up there with Copland, Sessions, Barber, and Piston. Since then, his work has suffered from critical eclipse, in part due to the disdain of the post-Webernian serialists so dominant in the Sixties and Seventies, in part because he doesn't fit the music historian's "main line" of Modern American music, seen as stemming from Boulanger and Stravinsky. Harris did study with Boulanger, but in many ways his music bore the mark more of the Schola Cantorum – Franck and Dukas, rather than Stravinsky and Les Six. Harris's fellow composers didn't help. His Whitmanesque vision of the United States became unfashionable during the Fifties, and he turned into the punch line to jokes about the cluelessness of an outsized ego. About the only thing that has stayed in the repertory is his third symphony – a shame, since almost everything else I've heard by him shows at least a very interesting musical mind indeed. His music is defined by how it expands, rather than by the limits set on it. Harris has written of the great hold on him of the idea of "organic growth." His music typically takes a germinating idea and from it draws out a set of continuous variations. The variations tend to blend into one another, rather than stand apart, leading to a sensation of great intellectual power. Often Harris will group variations into large subsections, leading to a kind of trompe d'oreille. The listener can make analogies to classical forms like sonata, rondo, scherzo and trio, and so on, but the driving engine of the music remains almost always continuous variation. The excellent liner notes by John Proffitt mention that the seventh symphony is based on passacaglia (essentially, variations on a ground, strictly repeated). One immediately notes the analogy between passacaglia and continuous variation. Damned if I can hear what the ground of Harris's passacaglia is, but I'll take Proffitt at his word. Again, far more important (and audible) to me is the continual transformation of the initial idea.

William Schuman studied with Harris. One normally talks of Schuman's break from Harris with Schuman's third symphony, but to me the influence of the older composer never left his student entirely. Schuman's idiom may be more astringent, the rhythms jazzier, the colors brighter (even glitzy – I think of a remarkable timpani solo seven or eight minutes in), and the ideas more directly and concisely presented (Harris is usually far more contrapuntal), but the deeper structural principles remain. Schuman's sixth also unfolds in one movement from a germinating idea and one thing seems to lead inexorably to another. However, the relations to classical structure lie much more in the open, and Schuman strikes me as more formally versatile and innovative, particularly in his late period. One notes things like his Concerto on Old English Rounds for viola and women's chorus, To Thee, Old Cause for english horn and orchestra, and some strikingly individual choral music. The composer bases his sixth on passacaglia, although not a strict one, and this time you can hear it. Not content with that, however, he organizes his passacaglia into a four-movement symphonic structure – allegro, scherzo, adagio, allegro, with extended introduction and coda. He also tends to emphasize and worry a few intervals as he constructs themes – in this case, a major second and a minor third. Contrasts of tempo and character are starker, more dramatic than in Harris, where you can often find yourself in the middle of a climax without quite knowing the details of how you got there. With Schuman, everything appears clearly, even austerely clear.

As I've said, Ormandy captures the nobility of the Piston, even though the details blur a bit. He also gets the power of the Harris (probably the most congenial to Ormandy's kind of music-making) and the grim moodiness and savage aggression of the Schuman. The Schuman, in particular, is one of those things you don't expect from Ormandy's Philadelphia. It requires a sharp, precise attack (not Ormandy's strong suit), but Ormandy comes close enough and puts out a lot of watts besides. Koch has a good version in stereo with the New Zealand Symphony, but Ormandy's still the guy to beat.

The sound is the dry, boxy one favored by Columbia throughout much of its history. However, the performers (and the music) win through, and the notorious tape squeal from the Schuman LP seems to have been eliminated in this transfer.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz