The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mendelssohn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

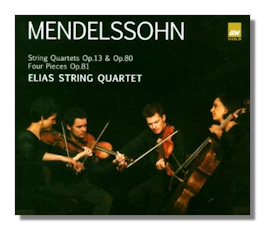

Felix Mendelssohn

Music for String Quartet

- String Quartet #2 in A minor, Op. 13 (1822)

- 4 Pieces, Op. 81 (1827-1847)

- String Quartet #6 in F minor, Op. 80 (1847)

Elias String Quartet

Academy Sound & Vision GLD4025 77:25

Summary for the Busy Executive: Prodigy and ex-prodigy.

Let's remind ourselves. Felix Mendelssohn was born in 1809. He never made it to 40. By the age of 15, he had produced masterpieces – the most astonishing child composer since Mozart. Indeed, his contemporaries thought of him as the Next Mozart. It turns out that nobody was the Next Mozart. Mendelssohn could turn out great stuff side by side with the not-so-great, and the latter appeared in noticeable proportion in his catalogue. Mozart wrote occasional well-crafted dreck as well, but hardly anybody knows it or thinks it worth their time to seek it out or to listen to it. Mendelssohn's fault-finders, on the other hand, could establish a very large club. Most of them follow the lead of George Bernard Shaw, who regarded Mendelssohn as stifled by Victorian propriety. A friend of mine, knowing of my admiration for Mendelssohn, once described his music to me as "a lot of notes played very fast," a charge, I may add, not entirely without foundation.

Yet Mendelssohn at his best, or even near it, still astonishes. Few composers of such finish have taken such chances or experimented so boldly. That most of these experiments fly by unnoticed usually means that Mendelssohn has succeeded in making them sound "natural." Some of his choral music – for example, the German Sanctus, "Heilig" – plays with spatial music at least a century before our own avant garde. Mendelssohn in his teens was also one of the first to study and learn from late Beethoven. As a child, he played the later piano sonatas to Goethe and admonished him when the emperor of German culture, under the influence of his "musical advisor," Zelter, Mendelssohn's teacher, wrote off Beethoven's music as chaotic and muddled. Only kids are that confident.

Mendelssohn's orchestral works strike me as extremely spotty. Here, I tend to like what everybody else likes: the Midsummer Night's Dream music, the Violin Concerto, the Italian Symphony, the Hebrides Overture, Elijah, and a few others. However, I usually find him at his best in chamber music: piano trios, string quartets, string quintets, the Octet (of course), the Preludes and Fugues, standalone choral music, many of the Lieder ohne Worte, the cello sonatas, piano quartets, and so on. The problem is that there's a ton of it, not always accessible. I suspect not many have heard all six of Mendelssohn's string quartets.

The String Quartet #2, written at age 18, shows the influence of late Beethoven. Mendelssohn bases his thematic material on an original song, "Ist es wahr?" Everything in that quartet somehow relates to the song. Formally, it seems liberated from pure Classicism. Mendelssohn experiments. As in late Beethoven there's a lot of "learned" counterpoint here (something Mendelssohn was always drawn to), but as in the older composer, it serves new Romantic expressive ends. The first movement begins nobly and broadly, and yet before you realize it, you've landed in the middle of a tempest, with little idea of how you got there. Fairly substantial, the movement flies along, thanks in large part to Mendelssohn learning something about "iconic" rhythms from Beethoven - in this case, dotted eighth plus a sixteenth plus a quarter (tan-ta-ra), which flows through the entire quartet. The climax erupts in a riot of free counterpoint. It seems like each instrument rages off to its own corner, and yet the whole makes sense.

The slow second movement shows Mendelssohn's daring. A radiant chorale begins it. Those who think of Mendelssohn as superficial have probably not heard this. From the chorale, it moves to a strange slow fugue, harmonically ambiguous and sounding fragmentary, although the counterpoint is certainly complete. Again, Mendelssohn learns something from Beethoven's example about turning a fugue into a dramatic, expressive statement, within the context of Classical forms. Mendelssohn's contrapuntal mastery allows him to turn the chromatic subject diatonic as well as to invert it. The chorale finally returns but with a difference. It brings along the fugal subject and reveals its thematic kinship.

The third movement, labeled "Intermezzo," is the simplest of the four, but that doesn't mean insubstantial. It starts with a memorable allegretto melody, moves to a presto scherzo-like passage, and ends with the allegretto and a surprise. Of course, if you've paid attention, you will hear its links to the earlier movements.

The finale – of the four, the most visionary – owes a lot to the late Beethoven quartets as well as to the Ninth Symphony. Mendelssohn gave the Berlin première of the Ninth at the piano and played violin in Berlin's orchestral première. A "crash" sends the movement off – a translation to string quartet of the opening chord of the Ninth's finale. The following violin recitative as well as the violin cadenza about two-thirds of the way through, point clearly to Beethoven's string quartet Op. 132. Also, as in late Beethoven, the movement tends to stop and restart. It's not a matter of copying or imitating. Mendelssohn has absorbed Beethoven's practice into his very original idiom. After the recitative, Mendelssohn explores the themes of the previous previous movements, but the second-movement fugue haunts the finale like an anxious spirit, popping up at the strongest rhetorical points. The violin steals in with its cadenza, tired to distraction. Just before the quartet seems about to gasp its last, Mendelssohn brings back the second-movement chorale, which restores health and serenity.

The second quartet mines deep, even though Mendelssohn was so young and so sheltered from hard knocks. The score has its tensions, but at a distance, much like the agitation of something like the Mozart g-minor quintet. However, Mendelssohn's last quartet appears after perhaps the greatest blow he ever received – the death of his sister, Fanny, in childbirth. Her death broke his health. He died after a series of strokes about 4 months later, in 1847. The fury here is personal and direct, and the composer concerns himself less with formal innovation as such. Far more dissonant than most of Mendelssohn, the score cries with heartfelt anguish in the form of successive minor-ninth chords. The second-movement scherzo has almost no development at all. Mendelssohn simply lays out the ideas and repeats them, as if to say what he has to say and get out. The spectral trio (with cello and viola in octaves throughout) sounds both angry and hollow.

We expect slow movements to express the greatest profundity, and by "profundity" we generally mean that the composer has somehow achieved the long view and has raised the personal to the universal. If so, Mendelssohn's Adagio will disappoint. The composer stands too close to his grief. There's an expressive confusion here, on the one hand idealizing the dead, on the other dazed and traumatized. I find it emotionally genuine.

The finale, contrary to Romantic practice, doesn't "resolve" anything. We return to the fury of the first movement, with the same loud cries. In a way, the main theme darkly mirrors the opening of Mendelssohn's Octet, but the sunniness of that earlier work has died. Its relentless rhythm (di-DI-di) reminds me a little of the tarantella finale to the Italian Symphony. If anything, it generates more power because, again, there's almost no fat here and very little classical development. Mendelssohn has stripped the music down practically to its skeleton, so that fewer notes make greater impact.

The 4 Pieces gather fugitive movements (Fugue in E-flat, Capriccio in e, Theme and Variations in E, Scherzo in a), ranging from the 1820s to the last year of Mendelssohn's life. Scholars, however, speculate that the final two of the four would have found their way into a seventh string quartet, had the composer lived long enough to complete it. Some of the four occasionally show up on recordings of Mendelssohn's complete quartets or whenever an ensemble wants to release a "light" album (viz., the Juilliard String Quartet's Miniatures for Strings on Sony 77118). The Fugue (1827) again shows Mendelssohn's immersion in Beethoven – contrapuntal technique in the service of serene expression. The Capriccio (1843), from the same time as the Cello Sonata #2 and most of the Midsummer Night's Dream incidental music, takes the form of slow prelude and busy allegro fugue, reminiscent of the fairy music of MSND. Theme and Variations (1847) stands as Mendelssohn's sole variations movement for string quartet. It shows Mendelssohn's new-found powers of concentration. The Scherzo (1847) has obvious links to the MSND scherzo. Mendelssohn put his own stamp on this genre, usually a mixture of elfin lightness and suavity.

Universal shut down AS&V in 2007 when it bought the label. Some of AS&V the catalogue shows up on the Sanctuary label. Unfortunately, this disc ain't one of them, as far as I know. I rarely write about non-current discs, but this one's a honey. The Elias String Quartet, a youngish group, plays with fire, ensemble sensitivity, and real understanding of an under-appreciated master. I especially like their Theme and Variations; they hit the right simplicity without condescension. They've obviously thought long and hard about these scores. They convince me that the second string quartet is a flat-out masterpiece. The recorded sound is superb. For kids of all ages, as they say, but especially for fans of string quartets.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.