The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

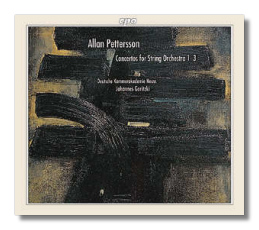

Allan Pettersson

Concerti for Strings

- Concerto for String Orchestra #1

- Concerto for String Orchestra #2

- Concerto for String Orchestra #3

Deutsche Kammerakademie Neuss/Johannes Goritzki

CPO 999225-2 2CDs

An easy way to tell someone about a new composer is to talk about who he or she is like. Unfortunately, Pettersson is sui generis. His music, his raw material, his attitude toward his material, and his methods resemble only themselves. People generally know him, if at all, as a symphonist, but none of his symphonies unfold in a familiar way. I find him a major voice of this century. There are two major rhetorical movements in his work: a fury that spends itself; a fragile lyricism violently stamped out. If Nielsen is a supreme poet of psychological integration and transcendence, Pettersson sings of disintegration and injury.

As a Scandinavian, Pettersson, to some extent, was cut off from the great cultural centers of Europe and North America - Paris, Vienna, Boston, Berlin, London, Amsterdam, New York, and Chicago. Consequently, it has taken his work some time to penetrate outside his native region. Kierkegaard's work, for example, did not appear in English until near the end of World War II. Nielsen, despite sporadic performances outside Scandinavia, had to be fought for, mainly by conductors with some sort of career around the Baltic. Horenstein championed Nielsen, Doráti Pettersson. I have never come across Pettersson's music in a live concert. Again, I thank whatever gods may be for recorded music.

Pettersson doesn't make things easy on performers or listeners. He demands attention from both over a long stretch. The Concerto #1 for strings, nominally in three movements, is really a single-movement structure lasting about 24 minutes, while the Concerto #3, in three separate movements, has a slow movement almost half an hour long. My main problem in coming to grips with his music was this: although he keeps to tonality (very chromatic, however), he doesn't use tonality as other composers - that is, as an architectural principle. He never signals to a listener that a new section has started by anything as conventional as a modulation, and I'm not really aware of key changes as such in his music. As a result, I admit that the way his music moved threw me. He works with little bits of notes that form themes or, better, musical gestures which are almost constantly varied. This resembles somewhat Schoenberg's methods, but the texture and narrative strategies are Pettersson's own. After many intense listenings, I'm starting to appreciate that each string concerto essentially builds from its own very small bag of these musical bits. It's almost the equivalent of musical fractals.

But I'm a bit nuts about how things are put together. Still, a more important question remains: how do these pieces come across to someone "just listening." I can't really call this kind of listening recreational, any more than reading Thomas Mann or Tolstoy or Celan or Kinnell or Hall is as much fun as a Brazilian samba. It is, however, compelling listening. Because of the span of much of Pettersson's work, many people have compared him to Mahler, but that' s not quite right. The composer that keeps coming to my mind is Beethoven, mainly for the sense you get of the composer's intense focus and attention on whatever is musically going on with the piece and how much goes on at any moment. Textures are spare and rhythmically charged. You sense that either something big is happening or about to happen. Also like middle-period Beethoven, Pettersson rarely takes his time. His length does not arise from a gradual unfolding but from an obsessional variation and recombination of material. Pettersson's music seems to me as vibrant and intense as the singing of insects.

The first concerto, according to the conductor Tor Mann, hit the Swedish musical scene with the "impact of a bomb." At the time, Swedish music was, for the most part, stuck in Romantic, nationalist nostalgia or with thin-blooded effigies of Stravinsky and Hindemith. Pettersson tried something new, taking off somewhat from Schoenberg, but mostly hitting a new note. Critics and even composers were confused. It's an aggressive, in-your-face piece from its opening bars, and Goritzki and his troops keep up the intensity and weary lyricism throughout the piece. As I've said before, its three movements, played without a break, are essentially one movement taking from the same store of ideas. The second concerto, in my opinion, continues this vein, although it's a bit more "relaxed" - a relative term when speaking of Pettersson. At least, it's not quite so abrasive as the first, and there's a passage of deep, lyrical beauty in the slow movement, with a theme resembling the incipit of the "Salve regina" plainchant.

The third concerto runs longer than the first two put together. It also covers deeper emotional ground, due mainly to the 30-minute slow movement. Without confusing length for heft, this movement runs its remarkable course, with, again, characteristic Petterssonian emotional rhythms: despair leading to anger and obsession, with a heartbreaking lyricism occasionally and briefly striking like a momentary shaft of sunlight through a leaden sky. Nothing gets emotionally resolved. It grabs you like the Ancient Mariner and compels you to listen. When it finishes, it leaves you to deal with the emotions it has stirred up.

I find the performances remarkable in every work. It's not easy to play for nearly two hours as if your life depended on it, but the Kammerakademie seems to have pulled it off. The aggression in the music rubs as harshly as ground glass, and the lyricism, when it comes, breaks your heart. I can't recommend these two discs strongly enough, if Pettersson is already your thing. If he's not, perhaps this isn't the place to start. I'd go with the Barefoot Songs or with the Symphony #7 instead.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz