The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mahler Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

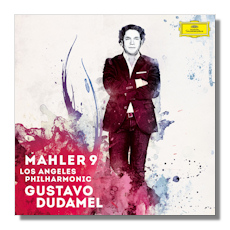

Gustav Mahler

Symphony #9

Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra/Gustavo Dudamel

Deutsche Grammophon 4790924 2CDs 86m

Gustavo Dudamel became music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 2009, when he was still in his twenties. The appointment was hardly a fluke as he was already an international star and arguably the most famous Venezuelan conductor of the day, maybe of all time. He has been garnering much attention in Los Angeles in recent years for his Mahler performances. His Mahler Eighth Symphony, for instance, was an extravaganza that featured over 1,000 performers. It drew high praise from critics and was quite an event to behold according to those in attendance at the concerts.

But how does the equally complex Ninth Symphony, the polar opposite of the ecstatic Eighth, do in his hands? Dudamel's Ninth features rather broad tempos and a strong sense of interpretive maturity, not the kind of qualities you'd associate with a conductor in his early thirties and still in the early stages of his career. His way of phrasing and shaping the score here would also suggest an older mind at work. This is not to suggest the score is short on freshness or is in some way lackluster: Dudamel realizes this is a symphony born of desperation and angst, and he's clearly decided on plumbing it for all its profundity and emotional depth, and he finds those qualities in abundance in this vital, dynamic reading. That said, he brightens the mood a bit in the inner movements with a spirited sense, his tempos falling well within the range of what one would term moderate or even lively. Moreover, he doesn't shortchange the acid-drenched character of the Rondo-Burleske. And listen to the opening of the second movement, how Dudamel subtly imparts a sense of uncertainty when the strings first dig into to the main theme with a hint of hesitation.

This is not to suggest that the outer movements are less effective in some way: Dudamel fully captures the sense of struggle and grimness in the first movement, and delivers a searing account of the death-obsessed finale. Notice that in the return of the first movement's main theme following the heartrending climax (which features drums that emphatically pound out that arrhythmic heartbeat motif from the symphony's opening), Dudamel is right on target, soothing the ear with a gentle, consolatory statement of the main theme and then moving on to a tense development of it, before finally relaxing to an unsettled sense of sadness.

In Dudamel's hands the finale is eerie and dark – but also tentative and mysterious, as if we're proceeding toward a dark corner, around whose turn lurks some great unpleasantry. Gradually, Dudamel builds tension in the finale and the mood turns to struggle, then to desperate struggle, then to quiet resignation in those fading, consoling strings.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic plays with utter commitment and accuracy throughout, and the sound reproduction is excellent. Fans of Dudamel and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, will certainly want this recording. Mahler mavens will also find this disc of great interest, for while there are many great recordings of the Ninth by the likes of Walter (his 1961 Columbia Symphony effort, not his rushed 1938 Vienna Philharmonic account), Bernstein (twice), Pesek, Giulini, Nott and others, this one by Dudamel is imaginative and individual enough to cast a measure of new light on this complex masterpiece. Strongly recommended.

Copyright © 2013, Robert Cummings