The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bernstein Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

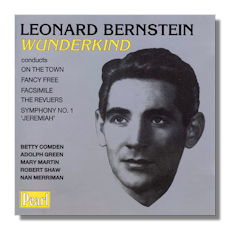

Leonard Bernstein

Wunderkind

- Sketches by The Revuers 1

- On the Town selections 2

- Fancy Free 3

- Facsimile 4

- Symphony #1 "Jeremiah" 5

1 Betty Comden

1 Adolph Green

1 Judy Holiday

1 Nancy Walker

1 Mary Martin

3 Billy Holiday

5 Nan Merriman, mezzo

3 Leonard Bernstein, piano

4 Sydney Foster, piano

2 Lyn Murray Chorus & Orchestra/Lyn Murray

2 Unnamed orchestra/Camarata, Leonard Joy

2 Victor Chorale & On the Town Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein, Robert Shaw

3 Ballet Theatre Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

4 RCA Victor Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

5 St. Louis Symphony Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

Pearl GEMS0005 134:18

Summary for the Busy Executive: Music man.

This two-CD set documents Bernstein's activities in the 1940s, when the composer was in his twenties. Bernstein landed in New York at the start of the decade and started to scrap his way to a secure career there. He began as a songwriter on Tin Pan Alley, with the byline "Lenny Amber" (in German, Bernstein means "amber"). He also worked night clubs as the musical member of The Revuers, a critically-acclaimed troupe that included such future luminaries as the writers Betty Comden and Adolph Greene and the actress Judy Tuvim, who later anglicized her name to Judy Holiday. This would probably have sufficed for most ambitious young men. However, Bernstein also conducted in New York and around the country and also composed concert works, including his first symphony – a fireball of talent.

The heyday of American cabaret occurred from the Thirties through the early Fifties with clubs like Café Society and Upstairs at the Downstairs (as well as Downstairs at the Upstairs), theater "gaieties" like New Faces and performers like Lena Horne, Jack Gilford, Eddie Lawrence, Lee Wiley, Slydini, Professor Irwin Corey, and the Revuers. Much of this material has disappeared – I hope only temporarily – and this CD gives us a chance to sample not only at somewhat sophisticated amusement but also to step back in time before theatrical humor became cloacal. We hear two Revuer sketches written by Comden and Greene: "The Girl with Two Left Feet" and "The Joan Crawford Fan Club." Both gently satirize Hollywood, warmups to the team's classic Singin' in the Rain. In "The Girl" Judy Holiday stands out as a gossip columnist named Miss Snooper and as the girl; few others could make a "nobody" comic without indulging in cruelty. Betty Comden plays several characters in the sketch (especially as Lamar Lamour, screen idol and the producer's wife), as does Adolph Green as the producer Cecil Moore DeB, et al. In "The Joan Crawford Fan Club," an acolyte (Betty Comden) expresses her doubts and her intention to ditch Joan, to the horror of her fellow members.

Bernstein's contribution as pianist and composer are able, but not stellar. Probably working at semi-automatic, he turns out songs strongly tied to the sketch, full of musical clichés (part of their humor), and practically designed to be forgotten. The music also, in lieu of scenery, efficiently sets the scene. Bernstein does best in the jazzier moments, where we get intimations of his first musical, On the Town.

On the Town burst onto Broadway during World War II. Three sailors on leave search for girls. In the background, never explicitly stated, lies the tragedy of young men going to war and not coming back. The show did respectable business and received decent reviews from the Broadway critics, although it didn't produce the critical gush that attended Rodgers & Hammerstein's Oklahoma! In many ways, however, it was much further ahead of its time, and one could argue that Broadway currently represents a retreat rather than an advance. In both theater and classical-music circles, it established Bernstein as somebody to watch. Musically, it established a new Broadway idiom – based in popular music and jazz (swing) but significantly apart from both. This mars the two recordings reproduced here. The first, from Decca, has the original players – Comden, Green, and the fabulous Nancy Walker – plus Mary Martin, whom Decca added for commercial appeal. Frankly, it's a mess. Walker and Martin get weak arrangements. As long as the orchestra plays something reasonably close to what Bernstein actually wrote, everything's jake. But whoever arranged "Lonely Town" for Martin made a hash of it, to the extent that he clearly didn't understand the song's tricky modulations. I cried when I heard Nancy Walker in her signature number from the show, "I Can Cook, Too." The musical featured a hot band – the record, a sweet and smooth one. It's like hearing a Lenny Bruce line delivered by Mitch McConnell. The second album, issued by RCA, features Bernstein conducting the "On the Town Orchestra" in instrumental excerpts and Robert Shaw conducting the Victor Chorale in the vocal numbers, with soloists drawn from the Chorale. Shaw's conducting and the Chorale's singing are professional, but they are caught in the soupiest arrangements this side of Campbell's, made mainly to give the choir something to do. Bernstein brings his trademark energy to the ballet music, but the orchestra has trouble with some of the snazzier rhythms. Incidentally, the best recording of On the Town remains the composer's own on Sony/Columbia, which reunites Bernstein with Comden, Green, and Walker reprising their original roles.

Bernstein's first classical hit, Fancy Free of 1944 was jointly created by the composer and choreography legend Jerome Robbins for the Ballet Theatre company. Three sailors on leave look for girls. Audiences loved it and quickly established it as one of the more successful American ballets. The ballet came before the musical and of course inspired the general setting, although the ballet is darker than the musical.

In a bar, a "down and dirty" jazz song plays on the jukebox. The sailors enter and see a pretty girl walk by. Two of the sailors take off in pursuit, leaving the third behind. Lo and behold, another pretty girl comes along and the sailor invites her into the bar for a drink. They hit it off. Meanwhile, the other two sailors return with the first girl and the problem of two girls for three guys. One of the sailors will have to drop out. They compete in a series of solo dances, which settle nothing, and they start to throw punches. The girls flee. The sailors stop and have another drink. However, yet another cutie walks by the bar, and the sailors are off again.

Normally, listeners hear Fancy Free in an abridged version. This recording represents not only the complete score, but the score in its correct order. Billy Holiday, backed by a jazz combo, triumphs in Bernstein's fiendishly difficult jukebox number, "Big Stuff," often left out of performances altogether – a mistake, as far as I'm concerned. Every other track was recorded in 1944. It took until 1946 before Holiday, after three tries, put down a version acceptable to Decca. The ballet dances to Bernstein's Big-City Boulevardier idiom: jazzy, melodically fresh. For the premiere recording, we get all of his jittery energy. The Ballet Theatre orchestra does well with the rhythms, especially as one remembers that they perform then-new music. Bernstein later led more polished performances. I prefer his stereo outing with the New York Philharmonic on Sony/Columbia. You get all of the vitality with more rhythmic and ensemble control.

Fancy Free's success tempted Bernstein and Robbins to make another ballet, this time serious in tone, which they titled Facsimile. It features an "age of anxiety" plot. A woman essentially picks up two men, who treat her with increasing roughness, until she shouts, "Enough!" The gloom and depravity of the action threw many critics off. They raked both choreographer and composer over hot coals, usually for pretentiousness. As a ballet, Facsimile hasn't seen many, if any, revivals, and this neglect has spread to Bernstein's score. I first heard it as a canned accompaniment to a screening of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (first time I ever saw the movie). Both the film and Bernstein's music bowled me over. The music marks an advance on Bernstein's "Jeremiah" Symphony and looks forward to the Symphony #2 (1949, original version). Despite its darkness, it still shows Bernstein's genius for memorable themes. Forget the plot. The music stands solidly on its own.

Again, Bernstein is his most persuasive advocate. He recorded the ballet for the first time in 1947 with an RCA pick-up orchestra. The recording has the merit of solid conviction of the score's worth. The orchestra stumbles a bit in the "Pas de trois" section, and the attacks come off a bit raggedy, although the orchestra pianist, Sydney Foster, does superbly in extended passages, not only rhythmically sharp but emotionally exciting. He doesn't just play notes. Bernstein not only keeps things going and together, he sets the interpretive pace, and with a pick-up group of players, to boot. I believe he made two other recordings: a Sony/Columbia stereo with the New York Phil and a late one for DG with the Israel Philharmonic. The New York outing isn't bad, but the sound is rather constricted. I prefer the Israel Philharmonic performance. It soars and, as a bonus, it sounds.

I have always regarded Bernstein as a major symphonist, if we go by quality rather than numbers. He wrote only three. The "Jeremiah" received the best reviews, although no one wrote that a new Bruckner had appeared. The reviews got more caustic with each new Bernstein symphony. The critics pretended to confusion (transferring it implicitly and explicitly to Bernstein as well) as to whether the Second Symphony, because of the extended role of the solo piano, was a piano concerto or a symphony – absolutely irrelevant to the proper critical questions: how does the piece work, how well does it satisfy its interior expectations, how high is its invention, and so on. It doesn't matter a whit whether you call it a symphony or a piano concerto, any more than it matters for the Brahms Double Concerto. The Third Symphony does suffer from a junky spoken text, written by the composer. On the other hand, it contains some of his best music. All three symphonies, however, carve out their own individual paths and represent highpoints not only in Bernstein's catalogue, but among American symphonies.

"Jeremiah" has three movements: "Prophecy," "Profanation," "Lamentation." Bernstein wrote the last movement first in 1939, just after he had nicked 20. It reveals artistic themes that remained with Bernstein his entire career, and certainly in his other two symphonies – namely, the concern for a society sick at heart. Each of the three symphonies reflects this in its own way: mythically ("Jeremiah"), psychologically ("Age of Anxiety", theologically ("Kaddish"). "Jeremiah"'s first movement, closely and powerfully argued, nevertheless contains high-quality musical ideas, and Bernstein has the gift of sticking them in your memory. The movement is mainly a dirge, with a tender chorale as a relief. It reminds me of the prophet lamenting the fate of Israel in exile and then suddenly recalling the city of Jerusalem. You get the same rhetorical effect in the Lamentations settings of Victoria, Palestrina, and Tallis.

"Profanation" functions as an angry scherzo. Themes from the first movement are recalled in a whirl of tricky rhythms and mixed meters. One phrase stands out, but only because of later circumstances. You hear the germ of West Side Story's "Maria" floating in and out in the trio section. "Lamentation" sets part of the Book of Jeremiah for mezzo. As I've said, Bernstein wrote it first, in 1939, and during the years between then and 1942 Bernstein learned a few things and honed his style. Its derivations from Copland and perhaps Bloch especially stand out more clearly, yet because of some personal alchemy, the whole impresses as an original Bernstein. Again, one notes the high quality of ideas. The mezzo There aren't many symphonies where the audience might hum the tunes walking out of the concert hall. The vocal quality of this symphony is especially hall.

Bernstein's recorded interpretation of this work didn't change much, if at all, over the years. Of the three recordings, I like the last one, with the Israel Philharmonic on DG, mainly because the sound blows the others away. The recording with the St. Louis Symphony is fine for a premiere, but a bit ragged, especially in the second movement, where the Bernsteinian syncopations occasionally fox some of the players. Nan Merriman, the mezzo soloist in the finale, runs into pitch problems. Sometimes she and the orchestra simply do not agree on the shared note. Tourel and Caballé don't have that problem – Tourel, because of her wide vibrato, which allows the listener to give her the benefit of the doubt (at least she's not obviously out); Caballé because she actually has the note.

Pearl specializes in important older recordings, and these performances appear in "historic" sound. The musicians sound constricted. I wish Pristine Classics, a label with a similar mission but apparently with more technical chops, could acquire the rights. The main reason for purchasing this disc would be for The Revuers sketches and for Fancy Free, the latter to hear Bernstein's full score in the proper order. For listening pleasure, however, I would recommend Bernstein's stereo discs.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz